Reading: Conclusion: Becoming the Father; Epilogue: Living the Painting (p. 120 to 139)

Perhaps the most radical statement Jesus ever made is: “Be compassionate

as your Father is compassionate.” God’s compassion is described

by Jesus. . . to invite me to become like God and to show the

same compassion to others that he is showing to me. (p. 123)

Heartfelt thanks to those of you who have continued to participate in our Lenten journey, those posting comments and those remaining silent. I have been personally blessed by the warm and comforting thoughts exchanged among our virtual community during a Lent unlike any we have ever experienced.

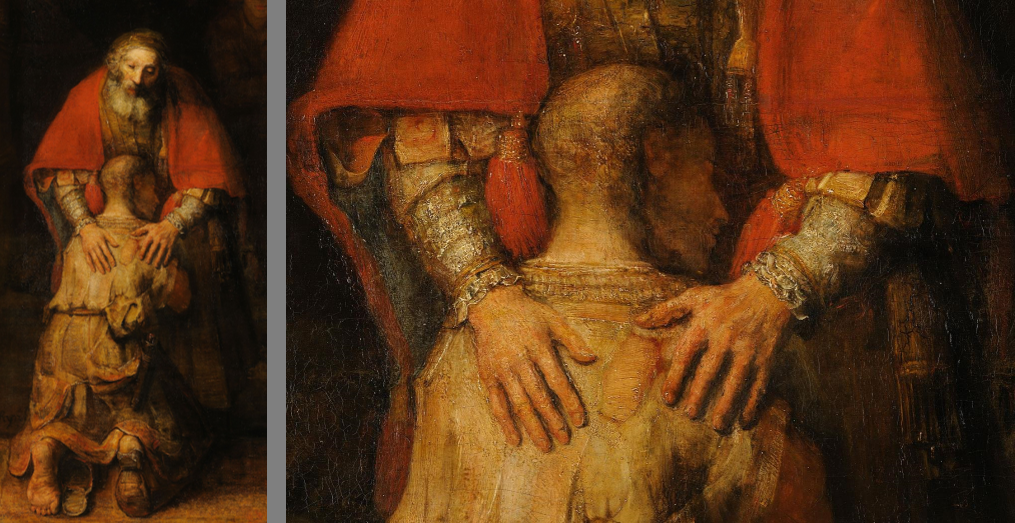

Adapting Henri’s words that open the Conclusion and making them my own, when I found The Return of the Prodigal Son by Henri Nouwen for sale outside the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd in Singapore in 2004, a spiritual journey was set in motion that led me to where I am in my life today. (c.f. p. 120) When I first read The Return during that most difficult period in my life I was, in Henri’s words, “. . . deeply touched . . . because everything in me yearned to be received in the way the prodigal was received.” (p. 134) Reading The Return again this Lent–16 years later and for the third time as a participant in these discussions–my perspective has shifted dramatically and I better understand the challenge in the quotation above to “be compassionate as your Father is compassionate.” While I remain, and we all remain, the younger son and the elder son, we are all called to become the compassionate father. And this has never been more true than it is now in the face of the coronavirus pandemic.

Jesuit Cardinal Czerny recently tweeted, “During my years working on HIV/AIDS in Africa (2002-2010), I learned a helpful slogan ‘We are all infected or affected‘- so simple, true and challenging for the current pandemic, like the second half of the Great Commandment: ‘Love your neighbour as yourself.‘” In the Conclusion and the Epilogue, Henri shows us that to live as people who are “infected or affected” we must become the compassionate Father and live the painting by “sharing the poverty of God’s non-demanding love.” (p. 138)

In words of great poignancy as we are social distancing or sheltering in place, Henri says it is the “Father’s call to be home. . . As the Father, I have to believe that all the human heart desires can be found at home (p. 132). . . . Living out this spiritual fatherhood requires the radical discipline of being home.” (p. 133). Home is where we grieve for our lost and suffering children and brothers and sisters; home is where we welcome them with forgiveness and generosity when they return.

As we come to the end of The Return of the Prodigal Son, Henri ties together the threads of his spiritual journey in a way that encourages us to reflect on our lives and our call to “be compassionate as your Father is compassionate.” We have another great week of sharing and discussion ahead. You are invited to share what touched your heart this week or at any time on our Lenten journey. We look forward to hearing from you.

Here are several of Henri’s ideas that might prompt your thinking.

“(W)hether I am the younger son or the elder son. I am the son of my compassionate Father. I am an heir. . . . Indeed as son and heir, I am to become a successor. . . . The return to the Father is ultimately the challenge to become the Father.“(p. 123)

“(B)ecoming the compassionate Father is the ultimate goal of the spiritual life. . . . If God forgives sinners, then certainly those who have faith in God should do the same. . . . Becoming like the heavenly Father is not just one important aspect of Jesus’ teaching, it is the very heart of his message. . . . The great conversion called for by Jesus is to move from belonging to the world to belonging to God.” (p. 124-5)

“Jesus is the true Son of the Father. He is the model for our becoming the Father. . . . His unity with the Father is so intimate and so complete that to see Jesus is to see the Father. . . . In everything he is obedient to the Father, but never his slave. “(p. 126)

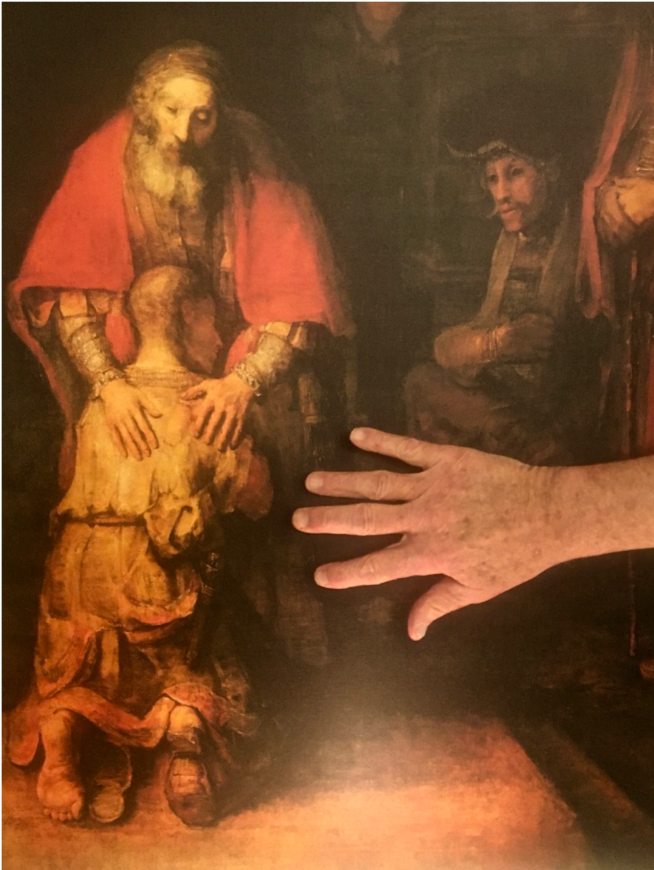

“As I look at my own aging hands, I know that they have been given to me to stretch out toward all who suffer, to rest upon the shoulders of all who come, and to offer the blessing that emerges from the immensity of God’s love.” (p. 139)

(I’m nearly a decade older than Henri was when The Return. . . was published. This image shows my 69-year-old hand and a detail from the poster hanging in our home.)

May the Lord be with you and give you peace.

Ray