Reading: Chapter 3 – The Writing Process

The Prodigal Son manuscript is in my humble opinion, not only your best book so far, but also a classic. It captures something so universal

and profound that it is truly a book for every person. (p. 81)

– Sr. Sue Mosteller to Henri, 1990

Thanks to each of you for another week of fruitful sharing. Now we are ready to move into the heart of Gabrielle’s book, to understand the process Henri used to write what Sr. Sue Mosteller presciently identified as a spiritual classic after reading his draft.

Based on her exhaustive research in the archives and conversations with those directly involved, Gabrielle Earnshaw powerfully conveys that the writing of The Return of the Prodigal Son cannot be separated from the life-changes, emotional and physical trauma and struggles, and painful and affirming personal relationships that occurred over the book’s nine-year gestation. She provides new insight into Henri’s deep depression and recovery that allowed him to find a real home at L’Arche and ultimately resulted in his most influential work. As Henri himself wrote in 1987, “I am sitting in this small room far away from L’Arche trying to live through the experience of being completely lost. . . I want to write about this painting and the story it portrays.” (p. 69)

Gabrielle provides an in-depth look into Henri’s life and writing process during these crucible years, including his struggles and recovery, and the crucial role played by Sr. Sue Mosteller, CSJ — a close friend of Nouwen’s and a distinguished leader of L’Arche who was named a Member of the Order of Canada in 2019. Highlighting this chapter are several never-before published letters between Henri and Sr. Sue illuminating her influence on Henri’s life and the resulting book. “She was his new ‘father figure,’ but of a very different kind.” (p. 67)

The is so much in this rich chapter for our reflection. As always, we are most interested in whatever thoughts and insights came to your mind from the reading. Here are several excerpts and questions you might choose to consider.

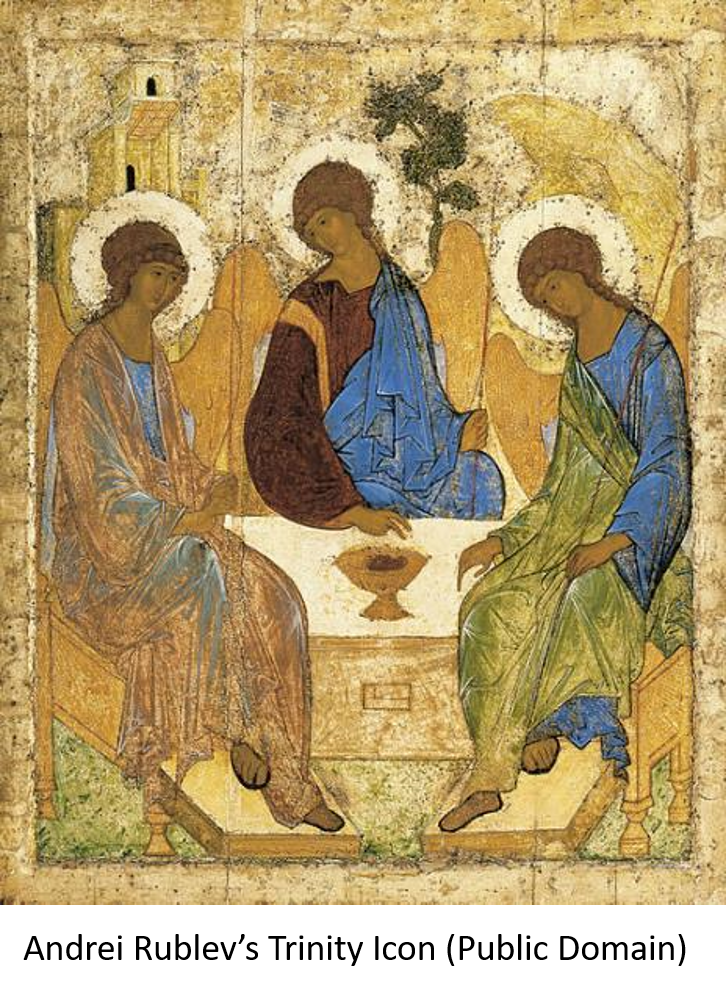

- This encounter. . . mediated through pigments and canvas was not just research. It was communication. It was as if the painting created a portal for a relationship that bridged time and space. (p. 64) Gabrielle calls this an encounter between Nouwen and Rembrandt. Was it really? Or was it an encounter between Nouwen and God, with Rembrandt in addition to the pigments and canvas as the mediator? Or was it both?

- Sue Mosteller. . . played the key role in his restoration to health. Indeed, much of Nouwen’s later contentment at Daybreak can be traced back to Mosteller. (p. 67) Sue wrote to Henri in 1988, “What I want to say is for you and your life today, where you are. I believe so much that the picture was given to you for your life and perhaps later for your writing. . . You have really “found yourself” more deeply there than anywhere. (p. 69) Henri Nouwen and Sue Mosteller share what Fr. Ron Rolheiser calls Real Friendship. In his book Domestic Monastery Rolheiser writes, “Friendship is more than merely human, though it is wonderfully human. When it is genuine, friendship is nothing less than a participation in the flow of life and love that’s inside of God.” Reflect on the friendship between Henri and Sue, her role as the “compassionate father” in Henri’s life, and how she helped Henri and Nathan to heal their relationship. Share your insights.

- In a letter to Daybreak leadership, Henri writes, I am deeply convinced that my writing about the Prodigal Son is for L’Arche and for Daybreak and is only possible because of my being part of this community. (p. 79) Why do you think Henri feels this way? How does he show it?

- The new theme that consumed him in 1992 was “being the beloved,” as explored in his book Life of the Beloved, published the same year as The Return. . . (p. 88) Gabrielle calls these still popular works “sister books.” How is theme of being the beloved related to story of the father and his two sons?

- The Return of the Prodigal Son shares many characteristics of the publishing zeitgeist of the early 1990s. . . But as much as it tapped into popular themes, (it) was not a runaway bestseller when it first appeared. . . In some ways, (it) was for people who had read the other books and were still hurting, confused, and/or searching for peace.

(p. 101) How is the The Return of the Prodigal Son different from other books of the time? Why has it retained its relevance for three decades while other seemingly more popular books have been forgotten?

We look forward to hearing whatever you choose to share.

May the Lord give you peace.

Ray

P.S. Looking ahead to the final week of our discussion — Gabrielle Earnshaw will be joining us for the final chapter and a look back at the entire book. She will be pleased to answer your questions as well. You won’t want to miss it.