Reading: Chapter 2 – Intellectual Antecedents

The Rembrandt painting became an icon for Nouwen, a gate through which he could walk into the house of God. But he could only do so because he

had been practicing that kind of seeing for a very long time. (p. 42)

What a wonderful first week of sharing! Thanks to each of you for your thoughtful comments on our reading and your kind exchanges with each other. It is rewarding to learn how Henri’s readers respond to Gabrielle’s insights and to see how that deepens our understanding of Henri and his work.

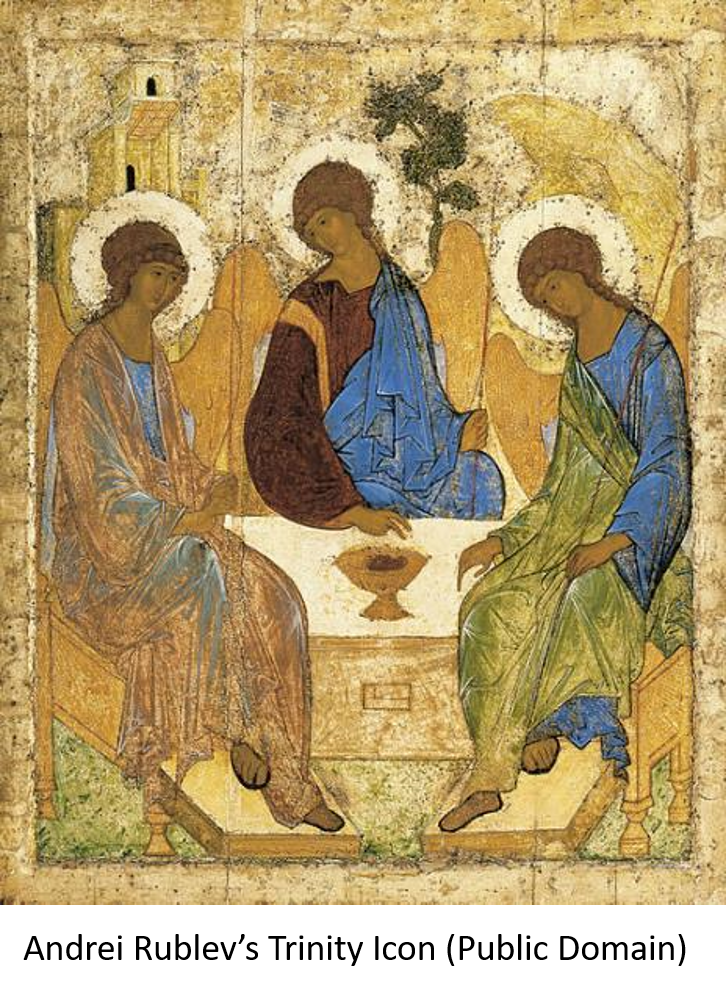

This week Gabrielle helps us “see” Henri and his spiritual classic in a new way by introducing us to the techniques and disciplines Henri himself practiced to “see” the world and its people. She probes how Henri’s refined ability to enter into a piece of art through the practice of visio divina or “divine seeing” empowered him to place himself into Rembrandt’s painting—first as an observer and then as each of the main characters. The icon to the left is the one that Gabrielle mentions as she begins the chapter.

Henri’s artistic vision was complemented and enhanced by his doctoral studies in psychology where he mastered the approach pioneered by Anton Boisen to see a person as a “living human document” where our life experiences are written. Henri’s profound insights about Rembrandt’s painting and his own journey result from his “divine seeing” of the “living human documents” that he encountered by gazing at Rembrandt’s masterpiece.

We have the opportunity to apply our newfound understanding of how Henri saw the world as we continue our summer discussion together. We are interested in hearing whatever you gained from the reading. Here are some excerpts and questions that might prompt your thinking.

- Nouwen was on the lookout for “glimpses” of God at all times. (p. 35) . . . (H)e didn’t simply see a beautiful painting–he walked through the gate and into the outstretched arms of the father. (p. 38) When and where have you seen “glimpses” of God on your spiritual journey? Is visio divina a prayer technique you use or might be interested in considering? When you are visit an art museum, are you more like Henri or Sue?

- Perhaps more suitable than any other definition of who he (Henri) was is the term “artist.” (p. 41) (Be sure to read footnote 37 too.) Gabrielle Earnshaw never met Henri Nouwen. She is sharing her insights after two decades of “living with” Henri’s work and speaking with many people who knew him intimately. Does thinking of Henri as an artist help you better understand him, his work, and his impact on you and other readers?

- “When I left I was very thankful that I had had the opportunity to meet this man whose suffering had become a source of creativity.” (p. 47) Gabrielle carefully reflects on Henri’s notes written after his visit with Anton Boisen. Does this give you new insight into Henri, help you to better appreciate the The Return. . . and the impact that book or other Nouwen books may have had on your spiritual journey?

- In seven important ways, Nouwen stood on the shoulders of Boisen while writing The Return of the Prodigal Son. (p. 57) Gabrielle briefly describes each of the seven themes where Nouwen built on the work of Boisen. What is your response to Gabrielle’s analysis? Does her assessment help you to better understand Henri and The Return of the Prodigal Son?

You are invited to share whatever is on your heart and mind–your thoughts on the reading, a reply to the questions, or a response to another’s comment. If you are following along silently, you are most welcome here.

May we all be blessed by another week of sharing.

Ray

I think when Henri left Dr. Boisen, he was deeply affected by having met in the flesh a deeply wounded healer. He had struggled with his mental health for many years, but had been able to begin CPE, in which students examine themselves deeply in order to keep their wounds from interfering with their ability to offer care. But for Nouwen, I think it was a bit backwards. He had written The Wounded Healer much earlier than Prodigal, and had an understanding, but had to be driven to his knees by the poster, when all intellect and the protection it afforded was stripped away.

I had a similar experience in my early 30s. I had not used my intellect but compulsive behaviors in an attempt to heal my wounds, living in constant fear of being found out. I was literslly driven to my knees and cried out, “I can’t do this any more.” And as the author so beautifully wrote, I who had been running away ran straight into the arms of God.

I am truly enjoying reading along with all of you. Your comments and insights are wonderful and I appreciate them. I have been struck by many of the same things that have struck some of you. One thing that I would like to add to the discussion is Henri’s idea of choosing what we see. Gabrielle writes:

“In addition to helping us pray when we don’t have words, Nouwen’s book [Behold the Beauty of the Lord: Praying with Icons] teaches us that we can choose what we see. We can take conscious steps to safeguard our inner space. Nouwen recognizes that we are bombarded with images, many of which are damaging, and we must be vigilant about where we put our attention. He writes, ‘It is easy to become a victim to the vast array of visual stimuli surrounding us. The “powers and principalities” control many of our daily images. Posters, billboards, television, videocassettes, movies and store windows continuously assault our eyes and inscribe their images upon our memories. . . .Still, we do not have to be passive victims of a world that wants to entertain and distract us. We can make some decisions and choices” (Behold 21). (Earnshaw 36).

I wonder what Henri would think of a world, which now includes all kinds of social media. We are bombarded with so many images that it is important for us to be on the lookout for the ones that can draw us to visio divina and on guard against those that would draw us away from the Father. In the midst of this challenging time of pandemic and unrest we see a lot of both. May our loving God lead us all to make lifegiving decisions. May we each and all find our Prodigal Son that we may know the Father’s love and live it into the world.

I found this chapter to be pretty heavy, with lots to ponder. First I learned about visio divina, divine seeing. I’ve had so much lectio divina the last couple of years I almost think oh no, not that again! But this was something brand new to me. However, I find I have been practicing it for a long time, I just didn’t know it! Deep prayer, without words, bringing me closer to God. And as someone who suffers from both anxiety and depression, kept under control by medications, my ears really perked up when I read “Depression restricts vision. I can no longer see the reality as God sees it.” I had never heard of Anton Boisen until now, and I see he was yet another great mind crippled by mental issues. For Henri to have identified so closely with him and looked up to him tells us a lot, especially after looking at the seven ways there are similarities. The most important of these I found to be 1) using his personal story to tell God’s story (not sure how I would have answered those questions Henri posed to his students!); and 7) Honoring the imago Dei.

After reading only two chapters, I am indebted to Gabrielle Earnshaw’s capacity to connect the dots of Henri Nouwen and create a clearer picture of who he was in light of his life longings. His quest for intimacy (home) and his deep ‘seeing’ seguaed into walking into paintings and living into people who were pieces of art too. Even when like Boison, their lives are born of terrible beauty.

Like Rembrandt who drew more than 90 self-portraits, Henri “wrote and rewrote his self portrait” (40). Henri was not a narcissist. Nor was his portraiture ego driven. It wasn’t fame he sought but a suitble frame for self-understanding. Of course this also aids understanding others as “living human documents” (45), and according to John Calvin is foundational to understanding God.

Henri not only repaints his own picture, but encourages others to “paint” their own life stories (41). The invitation stands–even and especially–when the picture isn’t pretty. Both Boisen and Henri suggest that suffering can become beauty: one a brilliant priest suffering with his sexuality; the other a renowned psychiatrist suffering with schizophrenia. Their stories pictures a permission giving paradox of beauty for ashes.

What a remarkable reversal of power. What a fearful invitation to us all. To think that it is in our very vulnerability that the grandeur of God finds it’s fullest expression. Instead of creating our own image, we are reframed in the Divine image. What a potrait to walk into. Is it worth the risk? It’s a terrible beauty and a terrifying invitation to go and do likewise…this idea that “My strength is made whole in weakness” (2 Corinthians 12:9).

Beverly, I have been holding onto the line you wrote: “…it is in our vulnerability that the grandeur of God finds it’s fullest expression.” It reminds me to stay soft, and to let go of my reflexive defense mechanisms–the layers of gunk I put on my own self-portrait–so as to allow God’s light and beauty to shine through, the Divine image that the Artist intended. Thank you.

Gabrielle’s descriptions of the seven themes and her ‘analysis’ really spoke to me in a deeply nourishing way, particularly the themes of “trust in the wisdom of wounds” and see “isolation as a form of suffering”.

Henri’s words: “God loves us with a first love…the second love (i.e., people)…CANNOT FULFILL MY HEART…” are truly shocking, heart-breaking and heart-opening. To know that this realisation comes with “enormous loneliness at times”, that “no human being is going to fulfill your heart”, that “you are really alone”, and that this aloneness is “good….because “that’s where God speaks to you” is profoundly sad, yet filled with hope, compassion, mercy and possibilities.

Henri then throws in another gem for healing and transformation when he states “that’s a loneliness you have to NURTURE, instead of trying to get over it”. After pondering these words numerous times, the following words eventually made their way into my mind: ‘Remember, it’s God’s love first, then other people’s. Our capacity to love and be loved will be limited as we are imperfect and wounded’. I felt like Henri was speaking directly to me, inviting me to ‘lean in…lean in some more…lean in further….and allow this existential loneliness to burn and transform you….and hang in there, allow this loneliness to run its course…allow it to make its way into your depths so that you really feel the full impact and beauty of this wound and suffering….and trust that your wound will eventually be transformed by the love, compassion, mercy and grace of the Holy Spirit’.

I intend to continue contemplating Henri’s words until I know they have truly landed in the depths of my heart and being. I am beginning to get a glimpse into the wisdom of this extraordinary human being and for this I am grateful. Thank you Henri and Gabrielle.

I absolutely love Earnshaw’s line that Nouwen “walked right through the gate and into the outstretched arms of the father,” (38) especially in light of today’s (June 23) Gospel reading which says: “Enter through the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the road broad that leads to destruction, and those who enter through it are many. How narrow the gate and constricted the road that leads to life. And those who find it are few” (Matthew 7:6, 12-14). Nouwen clearly found the narrow gate of the Rembrandt painting that led to tremendous life for him. I am struck, too, by the fact that Earnshaw notes that Nouwen’s kind of spiritual vision, his ability to “look at the world with the eyes of his heart” was a “practice he consciously cultivated” (38) and likely something that enabled him to enter through the life-giving narrow gate. He worked at it, which reminds me that I need to work with the gift of God’s grace and not just sit around and expect to be let in through the gate without some effort on my part.

Prior to reading Earnshaw’s work and participating in this discussion, I had not heard of visio divina, or the practice of thoughtful contemplation of a work of art, a picture, a photo or really, anything visual, that invites God to speak to us in a different way. In this period of quarantine, I have had the opportunity to spend a lot of time watching a pair of mourning doves build a nest outside my bedroom window. Both the male and the female carefully adding twigs and branches to build a nest, both parents taking turns sitting on the eggs throughout the day and night, and later both feeding and tending to the young hatchlings. At present, they are taking care of the third group of now fledglings who, having left the nest, continue to hang out and wait for regular feedings and care. Paying careful attention to the birds’ actions has been a gateway into prayer for me, an opportunity to consider how God has called me into being, carefully feathered my nest to ensure my safety and survival, and who even now nourishes me through Word and Sacrament and tends to my needs. Spending a lot of time watching and considering the action of the birds has drawn me through a gate of a kind into a new understanding of who God is. The authoritative, demanding God of my childhood has emerged as the One who cares for my every need and does not abandon me. And it is this same God who, along with Nouwen, is beginning to help me see that my own suffering and pain can be the seedbed of creativity and compassion; that suffering, pain and ultimately death is a reality we all live, but that new life and Resurrection is possible and awaits for those who are willing to step through the gate and into the mystery of God’s love and Divine life.

I guess I do practice“visio divina.” I am glad to know the practice has a name. My practice, however, is in taking in a spectacular vista in my neighborhood but then focusing on smaller details one at a time: perhaps the patterned wings of a hawk flying directly overhead or the tiny clusters of purple wildflowers just popping up on the ridge or two chipmunks playing tag. This morning it was a mama elk nursing a quite energetic baby. My focus was on the mother’s seeming patience and the baby’s excited wiggles while nursing. I think of God’s orchestration of the rhythms and cataclysms of the earth: photosynthesis, the cycle of seasons, gestation, the varied landscape created over time by geological fault lines, erosion, and storms. Doing walking meditations with a Native American guru on full-moon nights offers deeper, ancient connections with the land and the Creator. So many “Grand Canyon experiences,” as Henri said, in which we can “see our lives as part of something bigger than mere survival or worldly success.”

I love the assignment that Henri once gave his students to describe their “history with God.” How beautiful it is for me to consider where God has been present in my life and how sad to consider when God may have felt less present. How beautiful to consider that the kindness, love, and compassionate commitment of other people offer just a taste of the intensity of divine love.

One last thought: How wonderful that Gabrielle could devote such intensive time in getting to know Henri through her research, to carefully reflect on the meaning of Henri’s life journey, and to so beautifully share her findings with all of us.

In my freshman year at Yale Divinity School, to which Henri had just arrived from Notre Dame in 1972, I was a student in his course on pastoral care. What a course it was! I had expected to learn the “tricks of the trade”, to be trained in the clinical methods of giving expert care especially to hurting people. But instead, Henri used Boisen’s “case study method” simply to expose his students to the varieties of woundedness of people. One case study I will never forget was about Joseph Merrick, the original “Elephant Man”. I learned from that case study that there is no woundedness so ugly that it erases the image of God in a person. Henri asked us to read and discuss the case studies as a way of seeing every person as a “living human document”. Never during that course did Henri teach about methods of ministering to the wounded souls in the case studies. I was disappointed at first until I learned to value his reading of human beings as living documents that he had learned from Boisen and which I adopted as a lifelong practice in my pastoral ministry. He taught us to listen and respectfully see past the wounds to the unique and beautiful child of God.

What an authentic experience that must have been. Seeing with the eyes of God: “I learned from that case study that there is no woundedness so ugly that it erases the image of God in a person.” + “He taught us to listen and respectfully see past the wounds to the unique and beautiful child of God.” Profound, powerful insights and wisdom. Thanks for sharing.

In honor of Father’s Day, I find it imperative to share a few thoughts about my journey into the land of Henri Nouwen. I had read the Life of the Beloved and Wounded Healer in the late 90s and was deeply moved. Yet, it was the Return of the Prodigal Son that caused a major transformation and Epiphany in my life. I read the book during the summer of 2001. For me, it had a transformative effect in terms of my relationship with God. Though no longer Catholic, I had been raised Catholic even attending Catholic schools 4th through 9th grades. What moved me most about the book was the Unconditional Love of the Father. I was in my early 50s and transitioning into the role of the Father, yet I had much to acknowledge and uncover about myself.

The book caused an emotional upheaval in me that was unusual. I was reading the book during an airplane traveling trip from my Austin TX home to visit my oldest son in Kentucky. While sitting in the Nashville airport, I was overcome with uncontrollable tears and sadness while reading the book. What was speaking to me most deeply were the concepts of mercy, forgiveness, and the unconditional love and acceptance of the Father and God. This was not the predominant Catholic teaching in my early years of the 50s and 60s.

The primary reason I’m in this book discussion is that I was recently hit between the eyes with the following excerpt: Henri writes “I know the desire to be independent from a father who is strong, powerful, and dominating.” Bullseye, I could not deny who I was at 71 years of age. This was me, the type of father described. This passage gave me greater understanding and insight into what my three grown children and I are presently going through. Their ages are 43, 41, and 39. As challenging as it may have been for Henri or any child, it is equally challenging for a father or parent. My family and I are living proof as we transition through this phase.

What I’ve learned for certain is that parenting never ends, it just shifts form. It is an awesome privilege and responsibility. Yet, I press forward in continually growing into more of the Father of Unconditional Love and Acceptance as portrayed in The Return of The Prodigal Son.

Rodney, I am moved by your sharing and your honesty about your role as a strong, powerful, and dominating father and the impact that has had on your family. I agree with you: “it is equally challenging for a father or a parent.” We are imperfect human beings raised by other imperfect human beings and, for the most part, we all try our best. What a tremendous gift you are now giving your adult children as you continue to encounter the unconditional love and mercy of God, perhaps now mirrored through your adult children welcoming back their father who has been transformed by God’s abundant love and who can now generously share it with them in return.

Thanks, Michelle for your gracious feedback. Much appreciated! Indeed, “We are imperfect human beings raised by other imperfect human beings and, for the most part, we all try our best.” A wealth of Truth in that profound statement. Keen insight and wisdom.

It was very thought-provoking to me to read about the impact Boisin made on Henri Nouwen and the seven points of connection which Gabrielle lists. Especially since Boisin was Presbyterian Protestant and Henri Nouwen Catholic. I enjoyed reading about the commonalities. However, I am also glad that Gabrielle includes on page 56 and 57 “Boisen and Nouwen differed in one crucial way, however–how to relate God to the scientific method. Boisen pushed for a theology that documented the divine as an objective reality. Nouwen believe that there is something about the divine-human relationship that cannot be quantified…This argument for the validity of the heart experience over objective thought is a tension Nouwen lived with throughout his life. Boisen tried to bridge the gap by using science for theology. Nouwen was less comfortable with fitting God into a set of human-derived criteria.” My art obsession is the image of Jesus which Jesus dictated to St. Faustina. Have read numerous diaries and books, her confessor and so forth, watched numerous DVD’s about her life the impact of the painting of Jesus, pray all the time with my prayer cards and maybe I am selling my Protestant friends and family short but just would be very reluctant to ever share with them feelings and experiences with them. I think maybe for the same reason that Nouwen and Boisen diverged a bit in their spirituality too. That kind of observation made, I hope and pray that there will be some kind of Holy Spirit reconciliation among the parts of Christianity and Protestants will ultimately move closer to Catholicism and the “language of expression” will be more “normed” and “accepted and shared by everyone” so that Christianity seems more unified in Spirit.

Friends,

Charlie T posted a thoughtful and challenging comment on Saturday in the post for Week 1 and then he and I had a fruitful back and forth exchange. You might want to check it out. You can navigate there by clicking on the June 14th to June 20th link at the bottom of this post or by following the link in the upper right hand column to the June 14th to June 20th post.

Ray

Thank you, both Charlie and Ray…..both of you have allowed my own questions to surface and I feel prodded to wrestle more consciously with the complexities of the natural man/woman…human condition. I was not familiar with Boisen, but as I searched more info about him, I found he too struggled with mental health to some degree….he too, serves as a wounded healer. Anyway, I feel drawn to Deuteronomy 30 as I ponder the many paradoxes of life, and my own freedom to choose….turning and returning to Jesus, my ultimate Wounded Healer…….so much to learn, so grateful for this opportunity….keeping vigil with heart’s eye on the horizon (a thought I came across as I contemplated “gate”) as the loving father must have done and Loving Father continues to do……

Thank you Marge. I am pleased to know that our exchange has allowed your own questions to surface. The human condition provides a great deal to wrestle with, so keep at it. All the best.

Thank you, Charlie, for asking an interesting question about Henri’s homosexuality and what that might have meant to him in light of his vocation and concept of being a “wounded healer.” Prior to reading Earnshaw’s book and this discussion, I was unaware of Henri’s sexual orientation, and I find it particularly interesting given his relationship with his own biological father–the one with whom he felt he had to compete with in some way in order to be loved. Though he felt called to the vocation of priesthood, I am curious if his gender-orientation contributed to his sense of not belonging, of not measuring up in some certain way, especially given the time period and lack of any kind of real cultural acceptance as well. For me, it adds even more depth to Henri’s character and another layer to the internal and external struggles he faced. Thank you, Charlie, for your interesting comment and, Ray, for your thoughtful responses.

Thank you Michelle for your feedback. Henri certainly continues to trigger curiosity about so many things. This is what makes him so complex, fascinating and enigmatic. I feel like I am just beginning to understand him.